Overview

In the vibrant tapestry of Indian democracy, the electoral landscape unfolds with the precision and direction of the Election Commission, a federal body meticulously crafted under the constitutional framework. India proudly boasts of being the biggest democracy globally, and behind the scenes, there’s this dance between the central government and the states, all orchestrated by the parliamentary system. The Election Commission of India emerges as the guardian of fairness and impartiality, entrusted with overseeing and administering every facet of the electoral process.

As the exhilarating anticipation builds for the upcoming assembly elections in five Indian states—Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Telangana, Chhattisgarh, and Mizoram—a reminiscent journey beckons us to delve into the annals of history. In this article, we embark on a compelling exploration of India’s maiden election, untangling the intricate threads that intricately wove together the birth of the world’s largest democracy.

Forging India’s Democratic Identity: The Backdrop of the First Election of India.

In the initial draft of the constitution, there was a provision for a separate election commission for the central legislature and each state. However, a significant shift occurred during discussions, leading to the adoption of a new article on June 15, 1949.

This redrafted article proposed a single central and independent Election Commission responsible for all parliamentary and state legislature elections. The Constituent Assembly Secretariat, overseeing the electoral roll’s preparation, sought to conduct the first election promptly after the constitution’s enforcement.

The Partition refugees, lacking the necessary residency and citizenship credentials on paper, met disenfranchisement during the initial stages of India’s electoral process. With a minimum residency requirement of 180 days, these refugees, having recently arrived during the Partition violence, encountered a dilemma.

To address the issue, the Constituent Assembly Secretariat made a crucial decision, allowing refugees to be registered on electoral rolls based on their declaration of a permanent preference to reside in their towns or villages, irrespective of their actual period of residence. This measure sought to protect the voting rights of the disenfranchised refugees during this transitional phase.

The Secretariat maintained a firm stance that all adult Indians, regardless of caste, class, religion, gender, or any other identity markers, owned the right to be voters and should actively exercise this right.

The cornerstone of India’s electoral democracy lay in creating a comprehensive and up-to-date electoral roll based on universal franchise, uniting all adult Indians as equal participants in authorising their government. Amidst a civilisation divided by religion and language, the electoral roll signified the collective sovereignty of the people, developing a national identity of equality encapsulated in the phrase ‘WE, THE PEOPLE.’

The decision-making process for implementing a universal adult franchise faced a crucial choice when considering the integration of the electoral roll with the decennial census (census occurring every ten years). Despite initial suggestions, the Secretariat opted for the electoral roll to be a standalone entity, stressing its singular purpose and the need to foster trust among future voters.

The preliminary electoral rolls debuted in all Part-A states, excluding Punjab and Bengal, by November 1950. In Bengal, the rolls were published between December 22, 1950, and January 6, 1951. Notably, in Bombay, the rolls were initially published in Devanagari Script only. Still, directives were issued to publish them in English. Additional directions emphasised the publication of rolls in languages beyond the initial ones, especially in regions like Madras, Orissa, and Bihar.

The Election Commission, led by Sukumar Sen, took the reins in March 1950, actively engaging in the extensive design process. Values of equality, inclusivity, integrity, and secrecy of the vote became the guiding principles, shaping the meticulous preparations for the inaugural election between November 1947 and October 1951.

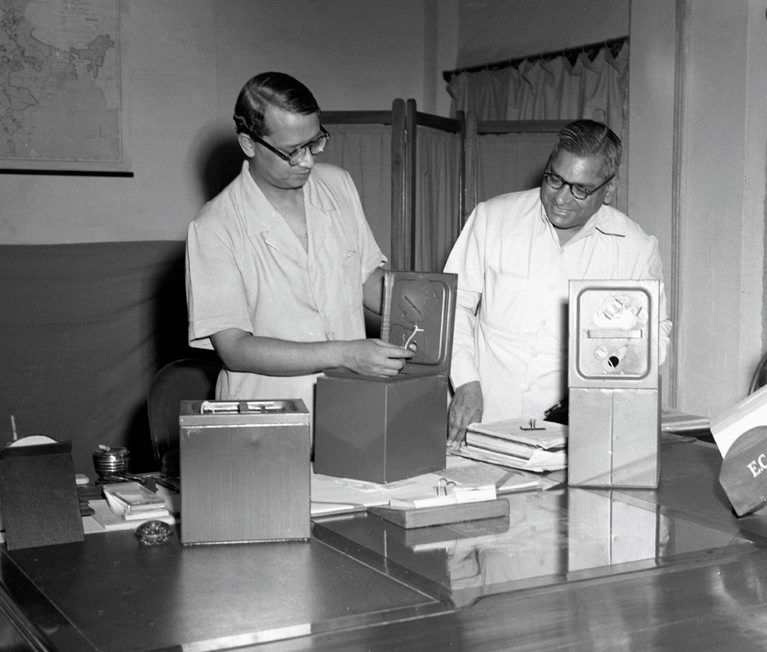

This period saw a focus on developing a secure and confidential ballot box, a critical element in ensuring the success of electoral democracy in the diverse and dynamic Indian context. The Election Commission, led by its chief, was deeply involved in refining the design of a ballot box.

This ballot box, crucial for ensuring vote secrecy despite widespread illiteracy and safety under Indian conditions, underwent numerous improvements. The final prototype gained approval only after rigorous testing, including experiments where the Election Commission filled it with up to 2,000 pieces of paper resembling ballot papers.

The thorough shaking of the box, designed with a slit approximately the width of a one-rupee note and ensured that no paper escaped.

Before its formal incorporation into the Representation of the People Act of 1951, the concept of using indelible ink to prevent personation and double voting was subjected to rigorous testing. The Election Commission collaborated with scientists from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), tasking them with enhancing the ink’s drying time.

Various attempts to erase the ink proved unsuccessful, demonstrating its resilience. Marking a voter’s finger with indelible ink has evolved into a mark of pride, prevailing for weeks after election day, serving as a lasting symbol of the democratic participation accomplished at the polling booth.

India’s Inaugural General Elections

The inaugural General Elections of India unfurled from October 25, 1951, to February 21, 1952, marking a historic chapter in the country’s democratic journey. The Indian National Congress (INC) clinched a resounding triumph, making Jawaharlal Nehru into the role of India’s first democratically elected Prime Minister.

Substantial characteristics of this electoral debut included the formation of the first Lok Sabha, replacing the interim legislature known as the Indian Constituent Assembly. Operating on the principles of universal adult suffrage, citizens aged 21 and above exercised their voting rights.

Fifty-three political parties vied for 489 seats, with the INC securing a sweeping triumph, claiming 364 seats. With a population of 36 crores, approximately 17.32 crores were eligible to vote, reflecting a 45% turnout.

Notably, prominent leaders such as Sucheta Kripalani, Lal Bahadur Shastri, and Gulzari Lal Nanda emerged victorious, shaping the political landscape of a newborn democracy. The elections also witnessed the participation of the Anglo-Indian community, nominating two members to the Lok Sabha.

Conclusion

In retrospect, the journey of India’s electoral democracy, marked by the meticulous efforts of the Election Commission, stands as a testament to the nation’s commitment to inclusive governance.

Today, as elections unfold in five Indian states, the democratic ethos resonates more vigorously than ever. Voting, once a privilege exercised by a select few, has evolved into a duty and a right for every citizen. The call to vote compulsorily reflects a collective understanding that active participation in the electoral process is not just a civic responsibility but a fundamental pillar of a thriving democracy. It is indispensable to remember that ‘WE, THE PEOPLE,’ are responsible for ensuring that.

Also Read: Millets 2023: Powering Sustainable Agriculture

Comments 1