Overview

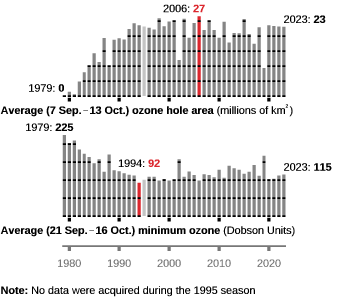

In 2023, the Antarctic ozone hole peaked on September 21, spanning 10 million square miles or 26 million square kilometres, as calculated by NASA and NOAA.

This substantial scale positioned it as the 12th most extensive single-day ozone hole since monitoring commenced in 1979, as revealed by annual satellite and balloon-based measurements from NASA and NOAA. As one delves deeper into the ozone depletion season, extending from September 7 to October 13, the hole consistently sustained an average size of 8.9 million square miles (23.1 million square kilometres), approximately reflecting the stretch of North America.

This extended timeframe solidified its position as the 16th largest ozone hole recorded during this period, underlining the ongoing environmental challenges in the Antarctic region.

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano, which erupted violently in January 2022 and unleashed a massive plume of water vapour into the stratosphere, is believed to have played a role in this year’s ozone depletion. The water vapour likely heightened ozone-depletion reactions over the Antarctic early in the season.

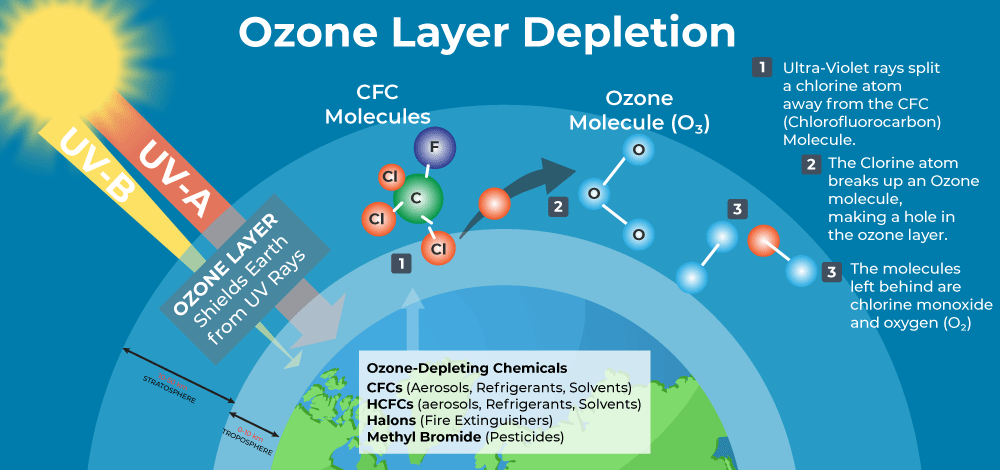

According to NASA, the breakdown of water vapour in the stratosphere releases reactive hydrogen oxide molecules that play a role in ozone destruction. These molecules also engage with chlorine-containing gases, converting them into compounds that further contribute to ozone depletion. Hence, a wetter Stratosphere will have lessened ozone levels.

Paul Newman, the leader of NASA’s ozone research team, said that if Hunga Tonga hadn’t erupted, the ozone hole would assumably be smaller this year. He acknowledged that they knew the eruption reached the Antarctic stratosphere. However, they cannot quantify its impact on the ozone hole.

Newman described the ozone hole this year as ‘very modest,’ attributing it to declining levels of human-produced chlorine compounds. He pointed out that, with assistance from the active Antarctic stratospheric weather, there was a slight improvement in ozone levels this year.

Antarctic Ozone Hole Depletion

What is Antarctic Ozone Hole Depletion?

The Antarctic ozone hole is described by the thinning or depletion of Ozone in the stratosphere over the Antarctic region during spring.

This atmospheric damage is a result of the presence of chlorine and bromine, originating from ozone-depleting substances in the stratosphere, mixed with specific meteorological conditions uncommon to the Antarctic environment. The region’s extreme cold temperatures, coupled with consistent strong winds, create a climate conducive to forming the ozone hole.

What generates the holes?

This depletion generally begins in August and persists until late November. During this period, the polar vortex, characterised by a mass of cold, swirling air, plays a crucial role. Warmer weather and ozone-rich air from outside the polar vortex disrupt the chemical reactions accountable for ozone depletion, leading to the dissipation of the ozone hole.

The direct contributors to these ‘holes’ are human activities emitting ozone-depleting substances, such as Chlorine and Bromine atoms, into the environment via practices like aerosol use, refrigeration and air conditioning. Ozone-depleting chemicals, mainly chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), have prolonged atmospheric lifetimes ranging from 50 to 100 years.

Despite the name, the Ozone hole is not a complete absence of Ozone; instead, the term serves as a metaphor for the region where ozone concentrations above Antarctica plummet well below the historical threshold of 220 Dobson Units.

The First Occurrence of the Hole

The initial reports of abnormally low ozone concentrations over the Antarctic stratosphere emerged in 1985, bringing awareness to the severity of this environmental issue.

Notably, the Antarctic ozone holes in 2000 and 2006 reached unprecedented sizes, extending over 29.8 and 29.6 million square kilometres, respectively—more than three and a half times the size of Australia. These massive holes even reached populated areas in Chile and South America.

While recent years have seen a reduction in the size of Antarctic ozone holes due to a decline in ozone-depleting chemicals, the potential for significant depletion in the future remains, especially with the ongoing accumulation of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Why is Ozone essential?

Ozone, a trace gas in the atmosphere at about three molecules for every 10 million molecules of air, plays a paramount role as a protective shield for life on Earth.

Ozone operates like a sponge; the ozone layer absorbs radiation from the sun, specifically Ultraviolet radiation (UV light), which can harm living organisms. UVB, a type of UV light, is known for causing conditions such as sunburns and skin cancers like basal and squamous cell carcinoma.

Comments 2